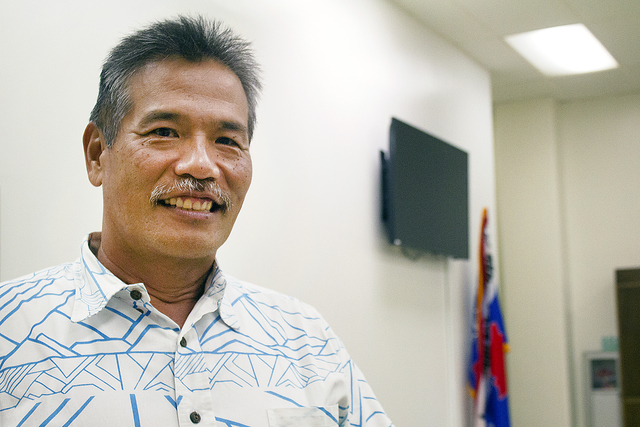

Police Chief Harry Kubojiri leans his chair back in his stripped-down office and contemplates, for the first time in almost 38 years, a life off the force. ADVERTISING Police Chief Harry Kubojiri leans his chair back in his stripped-down office

Police Chief Harry Kubojiri leans his chair back in his stripped-down office and contemplates, for the first time in almost 38 years, a life off the force.

Come January, Kubojiri, 58, will be retired and ready for a life of leisure, at least for a while. He’s already packed most of his personal effects, and boxes are stacked along one wall.

Rest, family, fishing and golf are in his immediate future, he said Thursday.

After that, maybe he’ll look at a part-time job or volunteer work.

“This job has taken a lot out of me,” Kubojiri told reporters, saying 12- to 14-hour days on weekdays and five or six hours on weekends takes its toll.

When Kubojiri started as a recruit in Kona, typewriters, onionskin and carbon paper were the norm. He wielded a six-shooter, had a bulky radio and carried a can of mace.

There were 238 sworn personnel on the force, compared to 450 positions now. In all, he manages a $65 million annual budget and 735 civilian and sworn positions.

The population of the island, at 92,000 in 1980, now stands at about 100,000 more than that. Two-page reports have morphed into eight pages.

Kubojiri, who became chief in late 2008, said he’s not recommending a replacement.

“I’m going to leave that to the Police Commission,” he said.

Tapping someone from within the force is preferable to hiring someone from outside, he said, simply because they already know the community.

One of the problems, however, is that the highest-ranking police officials would have to take a pay cut to become the chief. The chief’s annual salary, set by the county Salary Commission, is $139,138. Other officers’ pay tracks with the union wage hikes set through collective bargaining, and they can make much more with overtime and holiday pay.

Transparency and accountability were Kubojiri’s main goals, he said, and he’s seen some success in both areas.

His biggest achievement, he said, was getting the department accredited by the Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement, or CALEA.

“We are following national standards. Everything we do can be explained,” he said. “Do we still make mistakes? Yes. But it’s less frequent.”

Kubojiri also instituted regular police-media sessions with a professional facilitator to improve communication between the two entities to foster a more cooperative relationship.

The Police Commission has routinely given Kubojiri high marks in his annual performance evaluations.

In a report released in June, Kubojiri was evaluated in three categories: enhancing open communication, managing staff and resources, and increasing professionalism within the department.

The evaluation, signed May 24 by Kubojiri and commission chairman Guy Schutte, doesn’t give a numerical grade, but includes the input of each of the six current commissioners. Three commission seats were vacant.

“He’s managing his staff and his resources well,” Schutte told West Hawaii Today at the time. “As with everything, there’s always room for improvement.”

Commissioners couldn’t be reached for comment by presstime Thursday. They were notified of Kubojiri’s pending retirement at a commission meeting last week in Kailua-Kona.

Overall, the six reviewing commissioners said Kubojiri was doing an “excellent,” “exceptional,” “incredible,” “very good” or “good” job in their unsigned evaluations.

The commission regularly sees a parade of complainants at its meetings, with people complaining about officers being arrogant and rude, using unnecessary force, yelling at people reporting crimes, profiling and harassing certain residents and throwing suspects in the mud.

Previous evaluations for the police chief encouraged him to get in front of community opinion, as the public didn’t seem aware that complaints and disciplinary actions against police officers have actually dropped.

Last year, two police officers were fired and eight other officers were suspended for misconduct ranging from improperly filing reports to failing to report to duty to displaying “overbearing conduct.” That compares with three officers fired and 17 suspended in 2014.

Kubojiri sees police body cameras as the police department’s next challenge. He favors their use, but said legislation still needs to be worked out about how much of the recordings should be made public, preserving privacy rights of suspects, victims and officers and how to handle storage and retention of the large video files.

“I’m a proponent of them,” he said, adding, “It’s not the silver bullet the people think it is.”